Paradoxically, the COVID-19 pandemic, unfolding since at least December of last year, underscored how capitalism has also engineered gigantic calamities: high-tech authoritarianism and surveillance; militarism (both in discourse and maneuver: there’s a war against the virus); states incapable of manufacturing — and hence turned to plundering — basic protective and personal hygiene kits (masks, gloves, toilet paper) as well as more complicated medical equipment (ventilators, oximeters); understaffed, underfunded, dilapidated and, in many places, nonexistent public healthcare infrastructures; precarious living (where your life depends on the monthly/weekly/daily/hourly wage that you’re making as an employee, or a freelancer in the ‘gig economy’); the failure to care for the sick and the vulnerable; the painstaking violence of value or the inability to consider humans outside of their function as workers enrolled in the capitalist economy (with work here, different from labor, as Hannah Arendt defined it, and corresponding to the artificial world of objects and commodities built by and through humans themselves); and last but not least, the tragedy of someone you love dying alone without you being able to have said your goodbyes.

In what it highlights and reveals, the COVID-19 pandemic (what precipitated it, aggravated it, how we got there, its current and future structural consequences, its boundaries) is not dissimilar to the launch, in 1957, of Sputnik-1, the world’s first space satellite that prompted Hannah Arendt to explore how intersecting forms of world and earth alienation threatened the future of life itself. Our contemporary condition arises precisely from the paradoxical relationship between technology, science, expertise, and wealth concentrated in the hands of the few on one hand, and human labor (as that which produces, reproduces and sustains life) on the other. If humans could go into space, if computer algorithms could make judicial decisions, if randomized controlled trials could determine how best to ameliorate global poverty, all this had also radically altered the realm of existential possibilities and made even more difficult older, more earthly, engagements with politics and worldly concerns. More than half a century after Sputnik, the COVID-19 pandemic provokes comparable questions, albeit posed differently: it lays bare the fact that how we organize and produce our societies and our world leaves us unprepared in the face of worldly threats.

On a smaller and more local scale, Lebanon is no different. In fact, it is the epitome of the fiasco. It is the debacle of the ‘glocalized’ (a despicable word) world that we have created for ourselves. A world broken constituted as it is of shattered and dysfunctional relationships between humans and non-humans (trees, rivers, bridges, dams, commercial malls, four-wheel cars, ATM machines, a kilo of rice, a high school diploma, the virus); humans with each other; and politics. If there’s one sector, one field of activity, where this is most obvious (even more so given the present circumstances), it’s the healthcare sector.

Public and private healthcare systems in Lebanon

Lebanon’s health care system is highly privatized with around 70 percent of primary health care centers and 80 percent of hospitals (including at least 8 university hospitals) belonging to the private sector. It is also fragmented as it is built around convoluted public-private partnerships with multiple sources for service delivery, funding, and stewardship (conducted by institutions which approve reimbursable protocols, establish recognized and authorized treatment courses) for patients.

Service provision and funding

Service providers include semi-autonomous public hospitals, not-for-profit private hospitals, for-profit private hospitals and over 700 primary healthcare centers and Social Development Centers providing primary healthcare services – 70 percent of which are run by NGOs (local and international) and associations affiliated with faith-based institutions or political parties. The Ministry of Public Health also oversees a network of around 220 clinics that offer comprehensive care packages – with sexual and reproductive health included – and that have been accredited by the Ministry. Funding sources are quite varied. They include but are not limited to the Ministry of Public Health, the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), the armed forces funds, public civil servants’ cooperatives, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and private insurance companies. Today, around 47 percent of Lebanese citizens have health insurance coverage. About 23 percent of those are covered by the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), 9 percent by military schemes, 7 percent by private insurance, 4 percent by the Civil Servants Cooperative, and 4 percent by other schemes. The remaining 53 percent lack any formal coverage and are covered by the Ministry of Public Health, which serves as an “insurer of last resort”. It is also worth noting, here, that healthcare coverage at the level of the primary healthcare clinics is covered through the Ministry’s specific program for primary care financed by the World Bank through a combination of grants and loans (150 Million USD).

There are other forms and sources of health coverage for non-citizens living in Lebanon. Palestinian refugees access health through UNRWA-run and/or funded healthcare systems including primary healthcare clinics run by UNRWA themselves, hospitals run by the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, and private or public hospitals inscribed in the Lebanese Healthcare System (and where treatment costs are covered through funds from UNRWA and their partners). As is now known to everybody, and for the longest time, UNRWA has been coping with repeated funding cuts, strained services, and discontinuity in programs. Syrian refugees access healthcare through the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) mechanisms of support, including partner international and/or local NGOs. They access the country’s different clinics that are supported by either UNHCR or NGOs. UNHCR also provides subsidized access to more specialized levels of care in Lebanese hospitals. Here too, there’s been a general trend: funds dedicated to care continue to decrease while private hospitals continue to reap profit off human bodies. On that point: migrant workers have no healthcare coverage beyond the kafala compulsory medical insurance. While it technically allows migrant workers with valid kafala papers to access essential care in public hospitals, the reality of their lived experience is otherwise. Apart from the support they get from certain NGOs, undocumented migrant workers have no healthcare coverage whatsoever. Last but not least, and with contributions from the World Bank Trust Fund for Lebanon (TFL), and the UNHCR, the Government of Lebanon — through the Ministry of Social Affairs — continues to implement the National Poverty Targeting Program (NPTP) already established in 2011 under the Lebanon Second Emergency Social Protection Implementation Support Project (ESPISPII project). This project involved social assistance to 40,000 extremely poor Lebanese households but also, among other things, health coverage for beneficiaries in public and private hospitals through the waiver of 10-15 percent co-payments for hospitalization.

Disaster capitalism: the Lebanese Civil War and the healthcare sector

The Lebanese Civil War had a tremendous impact on the country’s health systems. Between 1975 and 1990, the provision of health services by the government decreased tremendously. These long years of civil strife also led to the systematic destruction of the financial, infrastructural and institutional capacities of the public healthcare sector. In 1990, only half of the 24 public hospitals were left operational, with an average number of active beds not exceeding 20 per hospital. Public hospitals were destroyed, closed, left un-operational, doctors and nurses were burnt out and many had even fled the country. Conversely, during the war, there was also a mushrooming of clinics belonging to NGOs, various associations and political parties – these primary healthcare clinics slowly took over the services that should have been provided by the public sector. Even more so, UN agencies played a major role in designing and implementing essential health programs in joint coordination with NGOs. The medical activities of these centers depended heavily on the availability of drugs which were often donated by agencies such as UNICEF that used those drugs as incentives to encourage preventive programs among NGOs.

So, the war, in a way, precipitated the turn towards an all-encompassing privatization of the healthcare sector in Lebanon. While in 1970, only 10 percent of the budget of the Ministry of Public Health was earmarked to be spent on healthcare in private hospitals, it is estimated that nowadays more than two third of the income of private hospitals comes from public money. On the whole, the Ministry of Public Health also relies heavily on international funding and support. Some of the Ministry’s partners include multiple UN agencies, governmental agencies, EU funds, World Bank support and NGO intervention. As mentioned earlier, these partners operate at the level of the country’s clinics but also in ‘building the capacities’ of public hospitals. For instance, the Rafik Hariri University Hospital (previously known as Beirut Governmental Hospital or BGUH), which helps lead the country’s efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19, test and treat patients, relies on the support of organizations such as the International Red Cross Committee and Medecins Sans Frontieres.

Lastly, national debt, trade deficit, internal dissent, profound political disagreements and pressure from the private sector influence how the Ministry of Public Health’s budget is allocated and spent. In addition to the popular (often exaggerated) assumption that political parties use public funds for clientelist ends, private hospitals administrators, well-known and highly influential physicians, as well as drug importing companies play a substantial role in how funds from the Ministry of Public Health get disbursed: to private hospitals, to purchase drugs from companies like Mersaco, Fattal, Pharaon, Omnipharma and others. Drug companies highly benefit from the country’s private health landscape. According to figures from the Lebanese Customs, in 2014 for example, Lebanon imported $1.1 billion in pharmaceutical products. A total of ten companies control 90 percent of the market with only four of these companies controlling 50 percent of the market. This gives an approximate idea of the extravagant profit these companies must be making.

With or without COVID-19, is private healthcare criminal?

As Yanis Varoufakis put it, private healthcare is not only inefficient, it is also destructive. Every dollar spent on private healthcare detracts from our societies’ capacities to deal with pandemics. There is no argument for private healthcare and not only because it renders care expensive and inaccessible. At the heart of all of this are also questions concerning the meanings associated with health, disease and illness, what counts as important in our societies, how healthcare workers are trained, valued and remunerated, how expertise negates more general skills and knowledge, and how human bodies are considered. Private healthcare exploits human vulnerability in the face of death. Simply, it is the worst, most immoral kind of exploitation and dispossession (of one’s own body for the sake of profit). Lebanon is a case in point. With such a privatized and fragmented healthcare system, it is impossible to develop preventative and curative care frames of social health (of healthcare as right), let alone face a pandemic such as COVID-19. As mentioned earlier, the destructive capacities of private healthcare revolve around patients’ inability to afford and access care but also include a society’s very capacity to deal with a pandemic. Let us develop this idea further by taking two examples: the country’s testing capacities and the private hospitals’ refusal to take on COVID-19 testing and treatment of patients free of charge.

COVID-19 Testing

During the last week of March, the Lebanese Order of Physicians had condemned the COVID-19 testing that was being conducted by various private hospitals and laboratories across the country and had called on the Ministry of Public Health to urge companies importing the test to restrict sales to a handful of qualified hospitals. The Order also called upon the Ministry to cover the costs of those tests in private hospitals. The testing for COVID-19 is done using RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction), a technique that allows the measuring of the amount of the virus’s specific genetic sequences. RT-PCR is a highly sensitive technique that entails the use of different protocols, kits and types of probes (a molecule used to detect and identify the virus’s genetic sequences). It also requires quality control measures (testing and retesting to ensure that results are reliable) that are almost impossible to achieve when tests are being performed haphazardly. The risk and percentage of false negatives and false positives (of grave consequences in the case of COVID-19) are thus increased in such a healthcare landscape. It is likely that the official number of cases reported daily by the Ministry of Public Health is not as accurate as it could be.

As a follow up, and in a circular issued on April 3 2020, the Ministry of Public Health provided a list of 15 hospitals which it considered qualified to conduct COVID-19 testing using RT-PCR. A quick glance at that list reveals two more shortcomings: access to care and the transfer of burden on public hospitals. There are no hospitals for testing in the Bekaa region, the South, or Akkar. Only one of the listed hospitals (Rafik Hariri University Hospital – RHUH in Beirut) is a governmental hospital that provides the test for free. Patients who headed to the other hospitals had to pay for their tests. Patients who opted for testing at one of the country’s most well-known medical university centers in Beirut reported paying as much as LBP 160,000 to open a medical file (when they’re new patients to that particular hospital) in addition to LBP 200,000 for the actual test. Some patients were also asked to undergo and pay for chest x-rays. Similarly, RHUH director Dr. Firass Abiad declared on twitter that when RHUH testing capacities are overwhelmed, RHUH sends tests to the American University of Beirut Medical Center and to Hotel Dieu de France hospital (which belongs to the private Université Saint Joseph) as part of the governmental hospital’s collaboration in the struggle to address the COVID-19 pandemic – it is unclear whether RHUH and the Ministry of Public Health have to pay these two private hospitals for these tests.

Transfer of burdens

There are different ways of conceptualizing the collaboration between public and private healthcare establishments. In Lebanon, this collaboration looks something like this: the healthcare system is set up so that private healthcare institutions reap profit while dumping the financial and medical burdens and risks on governmental hospitals. The transfer of burdens is a frame through which one can explore the dynamics of the healthcare sector, like, for example, the hierarchical and gendered transfer of burden from physicians to nurses. In Lebanon, nurses are highly exploited, overworked and underpaid. According to Mirna Doumit, the head of the Order of Nurses, the salary of a full-time nurse can be as little as 700,000 LBP. With the country’s ongoing financial collapse, several hospitals have reduced nurses’ salaries and many nurses have already gone 5 or 6 months without getting paid. But our interest here is on the dynamics of the relationships between private healthcare establishments and governmental hospitals. In recent years, the Syrian refugee crisis had already deepened our understanding of how the transfer of that kind of burden occurs. Private hospitals although contracted by the UNHCR to treat Syrian refugee patients would often refuse admission for patients with high risk factors – as those could need intensive care, or could spend long stays in the hospital. There are many reasons for such refusal of admissions including but not limited to: saving limited bed capacities (especially in the intensive care unit) for patients who would pay higher fees; and avoiding the accountability for a spike in their potential mortality rates — which, as in the case of maternal mortality, for example, is something that is usually investigated by the Ministry. These cases often end up in governmental hospitals.

In the context of the Ministry’s nationwide strategy to address the COVID-19 pandemic, the Beirut Governmental hospital’s mandate is to providefree care for all. In theory, the country’s largest hospital (with a potential capacity of almost 600 beds) is a university hospital that is equipped to deal with complicated cases, and whose staff conduct medical research and are capable of providing high quality care and producing solid scientific knowledge. But the facts on the ground (and the flurry of fundraising campaigns meant to support the hospital) show that staff are overworked, underpaid, and exposed, that equipment is often lacking, and the general state of the hospital’s infrastructure is decrepit. Meanwhile, and at the time of writing, private hospitals continue to refuse free care for patients diagnosed with the novel coronavirus infection. Their argument: the Ministry of Public Health and the National Social Security Fund owes us overdue money for patients we treated ages ago. It is unclear whether they will refuse to admit patients outright should the Beirut Governmental Hospital become overwhelmed (and it might).

Several major private hospitals in and around Beirut have already announced having set up special wards to diagnose, care for and treat patients diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection. In a memo addressed to insurance companies (the majority of which are excluding COVID-19 related costs from their coverage – these companies’ contracts specify that pandemics are not included) and third-party private payers, one of those hospitals, a well-reputed francophone establishment in Beirut’s eastern suburb, listed the price of tests and treatment in their “flu center”. Prior to admission, diagnostic tests (various PCR tests, a thoracic scan, and a clinical consultation) could cost up to a total of USD 638$. After admission, every night spent in the hospital, notwithstanding the cost of medication, consultations, etc., would cost every patient: USD 1,000$ in an isolated room; USD 1,500$ in the intensive care unit when no ventilator is needed; and USD 2,800$ in the intensive care unit when a ventilator is used. Patients who are covered as part of the National Social Security Fund are granted a 30 percent discount. Additional procedures including extracorporeal oxygenation, a technique of oxygenating blood outside one’s bodythat temporarily plays the role of one’s heart and lungs when they’re not functioning adequately, is charged as a one-time intervention at a fee of USD $10,000. The crushing majority of the population in Lebanon cannot afford such care, even prior to the country’s financial collapse (let alone after the devaluation of the Lebanese Lira). These people will go to the Governmental hospital, even if it’s dilapidated.It is a hospital for the poor, isn’t it? But then what will private hospitals do if the governmental hospital is overwhelmed, overstretched above and beyond its capacity? Refuse to admit patients? Pull the plug when after two weeks in the intensive care unit a family can no longer cover the bill? There are no rights under capitalism, after all, only consumption. You get what you pay for. Deal with it. Move on.

If the world is broken, Lebanon is also shattered and on the brink of implosion. The novel coronavirus pandemic has come to exacerbate the effects of years of unabated exploitation, extraction and dispossession by the country’s oligarchs which have left the country in shambles. But as Adam Hanieh rightly observed, the world is somehow collectively sharing an experience of this kind. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and the unfolding global economic breakdown requires a global approach. Quarantine or not, we have never been more connected, but in ‘concrete terms’, where it really matters, we have never felt more alone. This is where we fall back on the conundrum wherein lies the crux of the matter: the paradoxical tension between science and technological advances on one hand, and our relationships to life and each other, on the other. There’s an unsurprising link to be made here with Arendt’s other much cited work on The Origins of Totalitarianism – where she argued that totalitarianism, as a political predisposition, is born from this very dialectical relationship. In their fight against the novel coronavirus, states have responded in increasingly totalitarian ways.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the many ways in which we suffer from a twofold alienation: from ‘nature’ (humans’ relationships with the environment) and from the social world we have created (the economic collapse) – if such a distinction is even possible. Politics is what mediates between the two. How do we stand in the face ofcalamities?How do we disassemble the World Bank? How do we dismantle the IMF? How do we prevent world capitalism, once more, from reinventing itself, from deepening, once again, alienation and heightening, time after time, inequalities? Is a world where, as Karl Marx said, each could become accomplished in anything they wish possible? In asking those questions, I am not interested in probing the pragmatics of policy propositions. Rather, I am looking to activate the work of the imagination so that other futures become possible.

At the very least, no one should die alone.

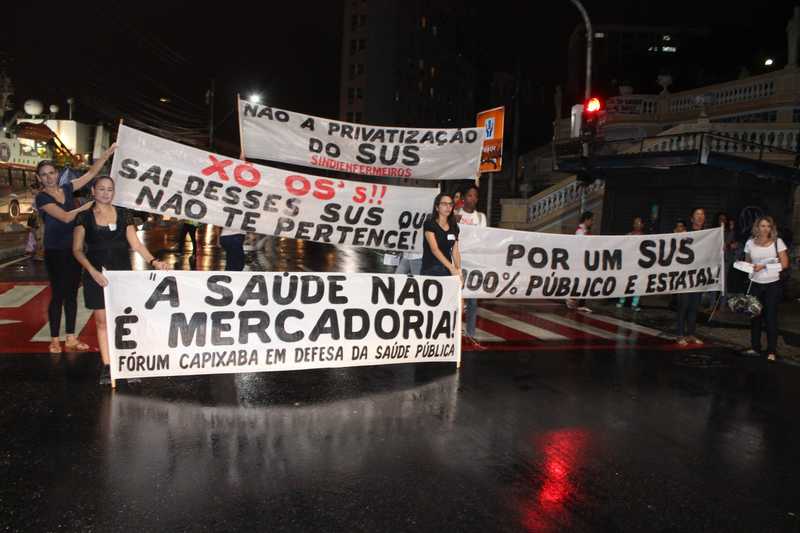

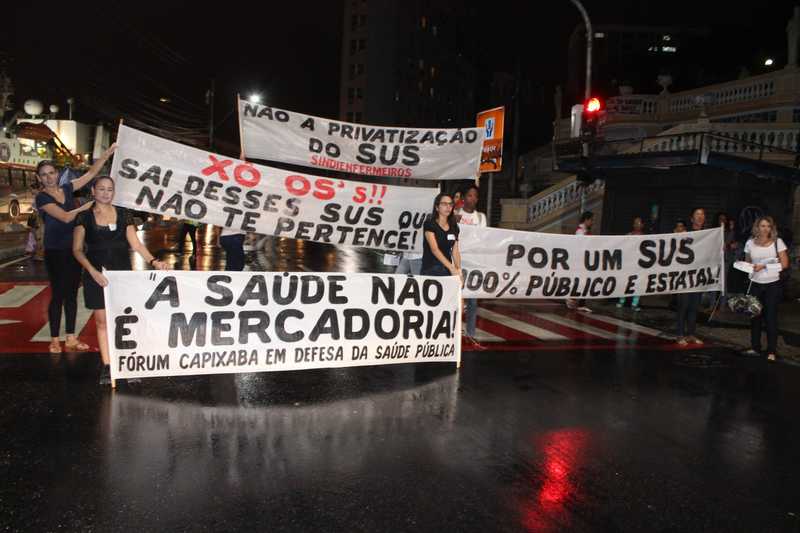

Photo: marviikad, Flickr